Invitation Dolly Gate Women With Butterfly on Her Dress

H er golden motorbus, Dolly I, is almost too brilliant to look at under the direct slap of a Tennessee sun. It is parked in a Nashville carpark, blinds drawn, the on-board air conditioner grumbling. Dolly I isn't as well travelled as its stablemate, Dolly II, which has ranged the motorways of Europe, and it doesn't have the political consequence of Dolly III, once refused entry to Australia on grounds of its size, before senior ministers intervened. But like those other buses, Dolly I cost its owner more than a million dollars and you'd better believe she's got it cool in there. When a security guard at the door shouts, "Dolly's coming off hot!" he does not mean that Dolly Parton – country musician, cultural matriarch, about to alight – is feeling toasty.

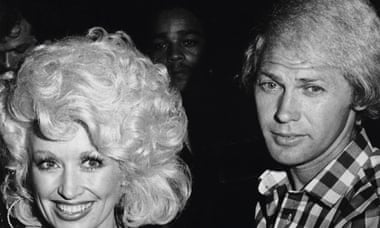

I am in a receptive semi-circle with members of her staff: a manager, two publicists, two assistants. They explain the terminology. Coming off hot? It means Parton's ready to go, in character, on. I am to expect her in one of the famous sleeved dresses, blond-wigged and bejewelled, topping 5ft in significant heels; the songwriter who perfected the expression of romantic impotence in Jolene, and the realist careerist who was fitful on cups of ambition in 9 To 5; the adored Nashville hero who inspired, above the bed in my hotel room, an instructional print asking the question: "What Would Dolly Do?" Here she comes, being helped down the bus's steps.

"Oh, look at my cute girls!" Parton says, spotting her young assistants. She patters across the car park. "Mornin'!" the assistants reply. "Don't you look cute?"

And she does: as neatly put together, as glowing and stable-seeming as the golden bus just departed. Her voice is still the honeyed purr I remember from the spoken-word opener of My Tennessee Mountain Home. That album, a masterpiece, came out in 1973 when Parton was 27. By 1980, when she was 34, she was being called "the Unsinkable Dolly Parton" by Rolling Stone magazine. And now here she is, 68 years old, still unsunk.

It's been a ridiculous year for Parton, her recording career turning 50 just as she enjoys unprecedented commercial returns from it. Her most recent album, Blue Smoke, went to No 2 in the UK in May, higher than she has ever climbed in the mainstream charts. In June she played Glastonbury – and snatched it, the festival's indisputable highlight. In fact, 2014 has been the culmination of a 10-year plan, I'm told by her manager, Danny Nozell, conceived "to try and put her back on top in the tail-end of her career". And already the next 10-year plan is being plotted: I hear talk of Wembley stadium, of a "Dollyfest" in Hyde Park.

Now Parton is in a period of calm, if not of rest. Her tour bus is parked outside a television studio where she'll spend the day recording a procession of commercials and bits to advertise the Christmas reissue of Blue Smoke. Parton's working – she's hot! – and she wastes no time, hurrying into the studio and sitting in an armchair beside a Christmas tree, where she records a video message for fans that will go on her website.

I am led forward to shake her hand: small, warm and weighted with clacking rings. "Oh, these are phoney," Parton says, her voice so soft I can hardly hear it. Cameramen are breaking down their equipment around us and I ask the studio manager if we can have the room to ourselves. "Uh, I don't know about that," he says. At which point comes a startling eruption.

"HEY EVERYBODY!" shouts Parton, a full and throaty Tennessee-mountain holler silencing the room. "WE'RE GONNA BE DOING AN INTERVIEW! AND HE'S TAPING IT! SO YOU ALL BE QUIET!"

"Is that what you were saying?" Parton asks me, sweetly.

Thanks, I say. And maybe we'd have a bit more privacy if people –

"HE NEEDS MORE PRIVACY!"

"Nah, I'm like you," Parton continues as the studio begins to empty. "I get scattered. My eye goes to where there's action and noise. You can't focus."

I am experiencing just this: difficulty focusing. At close quarters Parton is overwhelming, the mass of blond hair shaped today into a freestanding structure about the size of an archery target, the pillowy lips and the famous beauty spot drawing the eye. It comes as a relief when Parton again offers her ringed hand to demonstrate a point about longevity. Items of jewellery I can focus on.

"I've been around a long time," Parton says. "Long enough for people to realise that there's more to me than the big hair and the phoney stuff." She thumbs the ring, the "phoney" one set with a fake emerald. "The magic with me is that I look completely false when I'm completely real."

I wonder what the Parton who first arrived in Nashville back in 1964 would make of her now, with her career peaking in its sixth decade. "She'd think she's got more stuff." Would she offer any advice to her younger self? "Always keep the momentum going. I don't think you can ever stop." She says she's noticed that other careers in music have not proved as lasting as her own. "And people are bitter about it. But you'll find they stopped."

To do what? "To do something else. Whether it was a marriage, or whether it was deciding to stop and have children. That's all great. If you can make all of that work. But for me? I knew that I just had to keep going."

She says she got this work ethic from her father, Robert Lee Parton, a farmer who had 12 children with Avie Parton and raised his family in a cabin in the Smoky Mountains. "Ever since I was little," she says, "I've been like a horse with blinders." She remembers being eight or nine years old and suddenly being seized by ambition, a quasi-religious experience. "I didn't hear a voice, but it was a knowing that came to me, and it said, 'Run. Run until I tell you to stop.' And that's what it's been, I've kept on keeping on. And I never let a person, nor a thing, nor a sickness, nor a heartache, nor anything keep me from keeping on."

Later, her manager Danny Nozell confirms that being in the employ of Dolly Parton is not cushy. A fast-talking east-coaster with oiled hair, Nozell was once a sniper in the US army, but this, he says, is real work. He remembers watching Parton on TV when he was young and feeling the stirrings of a first crush. "Now she's like my mom. She scolds me when I need it. I'm 47, single, no kids, but y'know, I wake up every morning and love what I do. It's a 24-7 job. No pun intended, but 9 to 5 is an easy day."

This wasn't always the case. Dolly Parton's late-blooming career almost didn't happen. When Nozell met her in the early 2000s, she "hadn't had a manager in 17 years. She was kind of semi-retired, lying dormant." In 1999, Parton had been inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville, the sort of affirmation that might encourage any artist to slow a little. After a disastrous trip to London to gig at the Hammersmith Apollo (Parton was put up in a campervan for the night and the airport lost her passport), she had sworn off touring in Europe.

"Hey, she didn't need me to make money," Nozell says. "She was financially set. What she needed me for was to remarket her to the younger generation." He persuaded Parton to resume touring. Forget about campervans, he said: I'm assembling a luxury fleet. Dolly I, Dolly II, Dolly III were built and filled with familiar blankets, candles and her favourite earl grey tea. A 2007 tour of Europe sold out. A larger, arena tour the next year sold out, too. Parton went to Australia twice and sold out.

Though it's not uncommon for artists of a certain vintage to benefit from a late-career kick, particularly as a live draw, with Parton there was something else at play – a sense of novelty. Until 2007, she hadn't headlined a major show abroad. Some instinct of caution or condescension had always made booking agents put her on shared bills, a feature of package nights. Perhaps for this reason, Parton had long been saying no to festivals. Agents for Glastonbury asked her to play every year from 2006 to 2013.

The Glastonbury 2014 invite came with a polite warning: last chance. She said yes but remained uneasy right up until she took the stage. "Tense, nervous, wasn't sure I would fit in that crowd," she recalls. Immediately after the set, she was back on board Dolly II, driving away through Somerset under police escort. A BBC producer had sent the team away with footage of the gig and it was only after seeing aerial shots of the site, Nozell says, that she could comprehend "the size of the audience. This sea of people. She was blown away." An estimated 180,000 had gathered, the largest crowd for a performer in Glastonbury's history.

"I was walking down the street to the laundromat," Parton tells me, "and he stopped me." She's recalling her first week in Nashville 50 years ago. She met her husband, Carl Dean, within days of arrival. "He said, 'Hey, you're going to get sunburned out here!'" Parton chuckles. "Well, he had to say something."

Before Carl, she had had a boyfriend, Hollis, back in the Smoky Mountain town of Sevierville. After high school, Hollis took work at Sevierville's textile mill and stayed there until his retirement, 40 years later. Not for Parton. Her preferred distraction growing up was "a tin can on a tobacco stick", this artificial mic substituted for a real one as soon as possible. Within 48 hours of graduating, she was in Nashville, where she took work as a receptionist, occasionally filled salt and pepper shakers at a diner in return for free food, and began recording and distributing demos of her songs. When the country star Bill Phillips bought one, Put It Off Until Tomorrow, he asked her to share the vocals.

The industry met Dolly. Soon afterwards, she was cast on a country music TV show, which made her a household name. After departing the programme she released those deathless greats, Jolene, Joshua, Love Is Like A Butterfly, I Will Always Love You – the work she'd later refer to as "the old, sad songs". Periods away from country music in the worlds of disco (late 1970s) and Hollywood (1980s) yielded mixed results. The use of I Will Always Love You in The Bodyguard (1992) renewed her fortune. She founded a theme park, Dollywood, and a literacy charity, The Imagination Library. Quietly, along the way, she did what so few stars do and stayed married to spouse number one.

Carl Dean is not a musician or even, Parton tells me, musical. In their half-century of marriage he has rarely accompanied his wife on public engagements and there are precious few photographs of him. We have a sense of his character (a kindly and lethargic lug) only through the jokes Parton cracks at his expense. A member of her staff, though not one of the inner circle, tells me he has seen Carl only once, and Carl did not speak.

Was it considered unconventional, in the 1960s, that she didn't take her husband's name? "You know what," Parton says, "my passport is Dolly Parton Dean. I sign a lot of my contracts Dean. I didn't change names [publicly] because I already had a record deal. It made no sense. He never asked me to."

Has it been valuable, having that other private identity to retreat in to? "At home, to me, I'm Dolly Dean. But then I'm also Dolly Parton. I'm Dolly Parton Dean. I'm myself!"

Something – an adjustment in the chair, a re-angling of the head – warns me the tone is about to shift. "Anyway," Parton says, "if I had chosen the name Dolly Dean… I'd have been Double D. Again!"

OK, then. The boobs. I'd made a silent vow not to let them figure in this interview, simply because there is so much more that's impressive about Dolly Parton, even beyond the songs and the durability. She takes a proud, affirmative stance on gay rights (not insignificantly risky in the country-music industry), telling me: "People are gonna be with who they love, and they should be. I don't believe that we need to pass judgment." She's a knife-sharp businessperson and an influential philanthropist. She has been known to wake at 2am for phone interviews with journalists in far-away time zones – and guess which way round that arrangement normally works. The continual falling back on double-D groaners is just about the only lazy thing she does.

Sitting by the Christmas tree, when a pillow slips from her chair she gets mileage from the word pillows, and cracks an old joke about some people having known her back when she was a B-cup. What is this? A relic of coming up in the era she did, when it might have been expected she offer thigh-slappers about a visually distinctive body? Defensiveness, a preemptive fear of being mocked? Over the years, she has said she didn't feel pretty growing up. This was part of the reason for the big outfits, the bigger hair – a masking. I wonder if the reliance on innuendo is a masking, too: let's talk about my pillows, not the personality behind them.

Before meeting Parton I read her slim memoir, Dream More, which included a list of her favourite answers to often-asked questions. Impressively brazen, this, to publish your arsenal of non-spontaneous answers, particularly when you plan to go on using them as if they're fresh. That line Parton chucked me earlier, about looking completely false while being completely real, is the epigraph to Dream More.

Neatly written, droll, rarely revealing, the book had one passage that stood out a mile: Parton giving a commencement address to students at the University of Tennessee and being struck by sudden thoughts of the children she'd never had. I tell her I found that part of the book very sad.

"Yeah," she says. She seems to have a clear picture of them, these kids that didn't come. "You always wonder," she says. "My husband and I, when we first got married, we thought about if we had kids, what would they look like? Would they be tall – because he's tall? Or would they be little squats like me? If we'd had a girl, she was gonna be called Carla... Anyway, we talked about it, and we dreamed it, but it wasn't meant to be. Now that we're older? We're glad."

Why? "I would have been a great mother, I think. I would probably have given up everything else. Because I would've felt guilty about that, if I'd have left them [to work, to tour]. Everything would have changed. I probably wouldn't have been a star."

S ome prevailing rumours about Dolly Parton. She once entered a Dolly look-a-like contest and lost. She has a working bathtub on her tour bus. She keeps a bunker on the grounds of her Nashville estate that contains every dress she has ever worn, tens of thousands of them. Her body, underneath those carefully cut dresses, is covered with tattoos. She had an affair with Kenny Rogers, her duet partner on 1983's Islands In The Stream. She is a secret lesbian. She carries a gun.

The look-a-like story is true (Dolly overdid the makeup) and photographers, in 2012, did capture something that looked very much like a section of tattoo when Dolly wore a dress to a premiere that was slightly lower cut than usual. About a week ahead of my interview, Kenny Rogers undid 30 years of careful teasing and admitted, on US television, that he and Dolly never slept together. In the Nashville studio, her staff pass around a copy of the National Enquirer, muttering in amused tones about an old accusation repeated inside: that Dolly is in a relationship with her long-time personal assistant, Judy Ogle.

When I flick through the Enquirer, I realise, squinting at the fuzzy photographs, that Judy is the woman who has been circling Dolly all day, micro-managing the hair and keeping close during our interview. "I am not gay," Dolly told the website PrideSource last summer, adding that she and Judy shared "a precious friendship". When I suggest to Dolly that her non-famous husband seems like a stabilising force in her life, a rock, she corrects me. "God has been good to me. He gave me Carl Dean. And that was the perfect man that I needed. And he gave me my best friend Judy Ogle. And those two people actually have been the rock."

What about the other rumours? I ask Nozell. The dress bunker exists, he says. "It's like a weapons silo. Huge metal doors. You'd need to blow them off to get in there." And Dolly doesn't carry a gun, Nozell says, surprising me by pulling from the pocket of his trousers a loaded pistol, "because she doesn't have to".

We are chatting in the car park when he does this. Taking a look over his shoulder, Nozell gives me a nudge and says: "A quick peek. You've come all this way. You have to." And when nobody's looking he lets me climb on to Dolly's tour bus.

In among the long dress closets, the little tea bar, the double bed made up with purple sheets (a pair of reading glasses have been left on the mattress), I see a huge painted mural that depicts Dolly, smiling and bikini-topped, as a mermaid. Down the gangway, Nozell opens a door to show me the bus's working bath tub. We stare down at it – a ceramic hollow in the floor, two feet deep, not much larger than a washing-up bowl. "She gets in there," he says. This feels somehow momentous: Dolly has no prepared and published wisecrack, no song, about the little bathtub. Here is a piece of her life without cladding or costume.

And so much comes in cladding. During a recent gig, Dolly knocked over a bottle of water mid-set and said, "Well, my water's broke so I'd better deliver." She had a line prepared and ready for accidentally knocking over her Evian.

So, back in the Nashville studio, our interview gets a little fractious when I try to urge her off script. We're talking about the rumours, the ongoing speculation about whom she sleeps with. I ask if that has come to seem distasteful now that she's… "Old?" Dolly offers. "I'm 68, but I'm still sexy."

Is it distasteful? "Noooo," she says, sighing. "I think my life has been great. I don't care what people say about me, good or bad. I mean, you'd like them to say everything good, but I wouldn't want to be that vanilla. I'm glad [this is discussed]. Through the years, people must think I've really got around." She pauses and adds: "I guess I have, to some degree."

But Dolly, haven't we just been talking about your lasting, steady marriage? "Well, the steady marriage is one thing," she says, "but my flirtations, all that stuff, that's something else entirely. My husband knows I'm always coming home." What did she make of Kenny Rogers admitting their supposed affair was all a bit of a joke? "We could've gone down that road. And a lot of people do. And we probably have with other people. But Kenny's like a brother to me."

You have with other people? "Oh please," she snaps. "Everyone wants to get into the dirt. I wouldn't tell you if I had. How would I tell that? That would be all over the papers. That would be your headline, wouldn't it? 'Dolly admits to screwing everyone in town.' I'm not admitting nothin'. Maybe I did. Maybe I didn't. Maybe I will. Maybe I won't. And it's none of your damn business!"

We make small talk for a bit, recovering. Dolly says, sweetly, "You know I can't tell everything." We return to the What Would Dolly Do? print in my hotel room: is that a lot to bear, the comparison being drawn there? She says, "It's the greatest compliment in the world." I admit I've been thinking about trying to take it home with me and Dolly advises against it. "Now you know what I'd do. I wouldn't steal it."

"Are you a fan of mine?" she asks suddenly, as we're saying goodbye. How often can this question yield a negative? The songs that worm in and stay; those crisp slices of writing all through the catalogue, "the multi-coloured moods of love", "the lonely dripping down my face". Her verve and her intelligence and this brilliantly improbable late-career resurgence. The unsinkable Dolly Parton, at 68, went just over an hour on stage at Glastonbury without sitting or even slowing down. Yes, I tell her, I'm a fan. "Aw," Dolly says. "And I thought you were just a reporter. Well, that's great."

lopezthistagating.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2014/dec/06/dolly-parton-more-to-me-than-big-hair-phoney-stuff

0 Response to "Invitation Dolly Gate Women With Butterfly on Her Dress"

Post a Comment